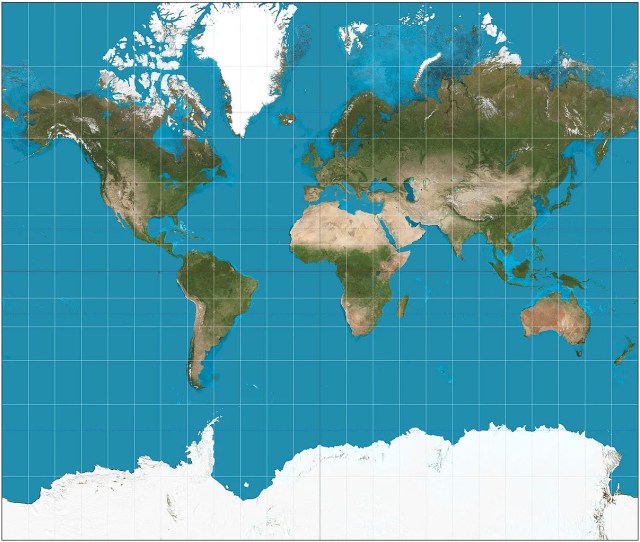

With constant coverage of Greenland in recent news cycles, the infamous Mercator projection has come under fire anew for distorting the real shape of the world’s continents — objects closer to the poles appear larger than they should. That results in North America looking larger than Africa, or China looking smaller than Greenland, when really the opposite is true.

Those criticisms aren’t wrong, but they ignore that the original point of Mercator’s projections were as a navigational tool for sailors. And, despite the map’s shortcomings, it remains extremely handy for that purpose.

I bring up Mercator and his controversial cartography because I was today years old when I discovered that the much maligned Belgian was the source of some truly wacky notions about the Arctic region and the North Pole that confused cartographers, geographers, and mariners for decades.

In 1577, Mercator wrote a letter the English scientist John Dee, in which he described the geography of the North Pole based on reports from a 14th Franciscan monk from Oxford, who travelled the North Atlantic region on behalf of the King of England. An account of his travels was published in a travelogue titled Inventio Fortunata (or “Fortunate Discoveries”), a book that has been lost for more than 500 years. However, a summary of this book was published in another travelogue called the Itinerarium by a traveler from the Dutch city of ‘s-Hertogenbosch named Jacobus Cnoyen. It was in Itinerarium where Mercator read about the astonishing claims made by the unknown author of the Inventio Fortunata.

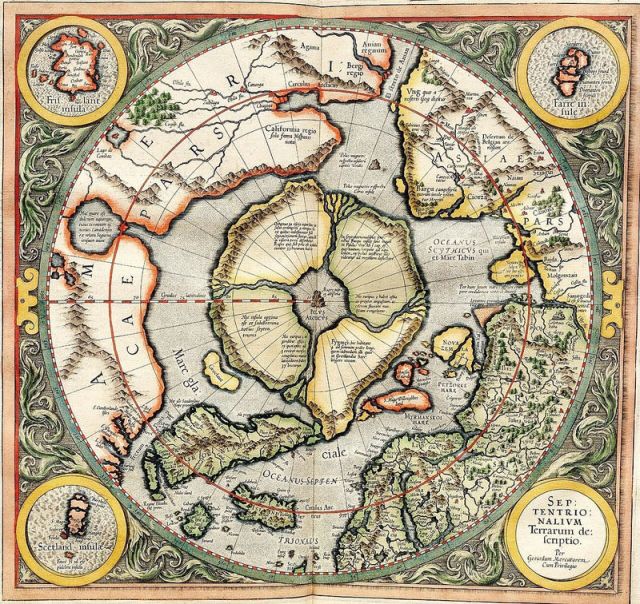

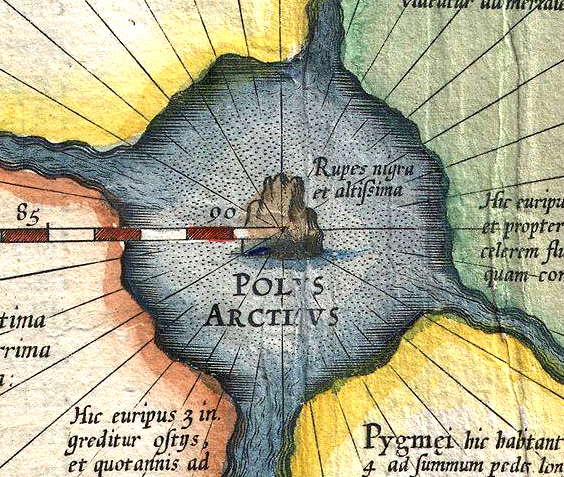

According to the account relayed by Cnoyen, the North Pole was a sea surrounded by four large islands with high plateaus and mountains. The islands were divided by massive rivers flowing inward forming a large whirlpool. At the center of this whirlpool stood a vast black rock, 33 miles in circumference. This rock was believed to be magnetic and the source of the mysterious attraction that pull all compass needles towards the north.

When Mercator published his world atlas in 1595—a ground-breaking work and the first collection of geographical maps to be called an Atlas—he included this black magnetic feature on his map of the North Pole, labelling it Rupes Nigra et Altissima, or “Black and Very High Cliff.”

Mercator also claimed that one of the four polar islands was inhabited by pygmies standing four feet tall, another detail drawn from the old English voyages described in the Inventio Fortunata. It is possible that the author of the Inventio was in fact referring to the indigenous inhabitants of Lapland, who are of relatively short stature.

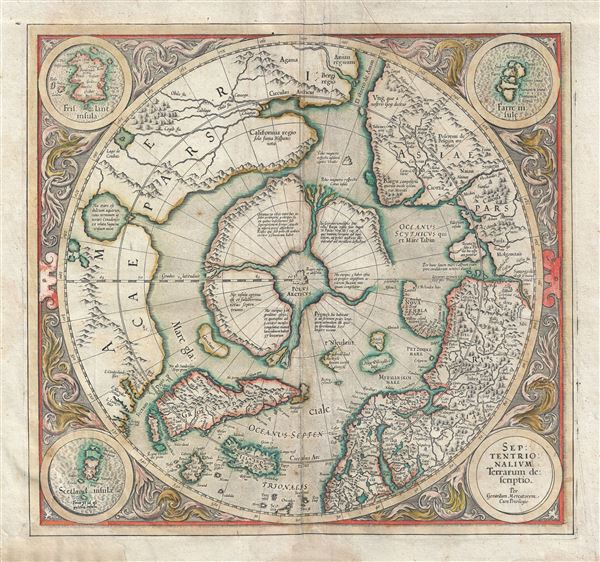

In 1606, Jodocus Hondius published an influential revision of the Arctic map, redrawing the four polar islands. Attempting to reconcile recent exploration with a century of established cosmographical tradition, Hondius removed part of the island marked Pygmei and replaced it with Nieulant, Willoughby’s Land, and MacFin—alternate names for Spitsbergen. The result was a map that attempted to hold two incompatible realities at once: the inherited four-island model championed by Mercator, and a newly revealed Arctic grounded in direct observation.

In the decades that followed, other cartographers adopted similar compromises. Gradually, however, empirical geography prevailed. By around 1636, all trace of Mercator’s four polar lands, the Rupes Nigra, and the Arctic maelstrom had disappeared from maps of the region.