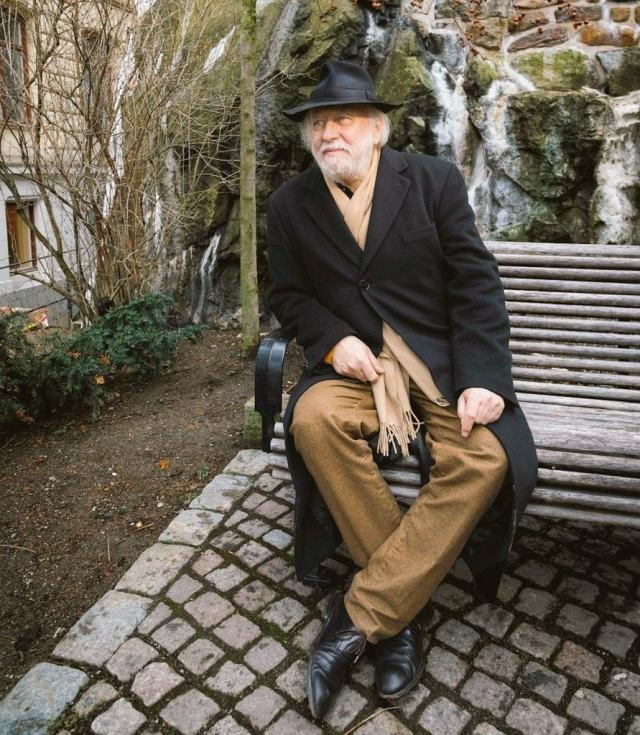

My name is Róbert Valzer and I like walking, not that I have anything to do with the famous Robert Walser, nor do I think it strange that walking should be my favourite hobby. I call it a hobby but I accept – or rather I am prepared to entertain the fact – that where I live in this Central European country I am considered to be too unstable to be regarded as a normal person and that my hobby is not to be compared with other people’s hobbies. It is not a hobby, they claim, but a symptom of instability. That’s the word they use: instability. But they never tell me that to my face. They whisper it behind my back. That’s what they are constantly whispering: I can hear them perfectly clearly – there goes Valzer, he’s off again.

But they are wrong even on this level because it’s not a case of going off again. I am always on the go, a walk not being the kind of thing to set off on, then stop, then start again, not in the least, because I have been walking as long as I can remember, having set off once a very long time ago and gone on walking ever since, which means I will go on because I can’t stop, because it is impossible to stop, walking being a passion with me, and what is more in my case, a passionate form of curiosity, not a matter of madness but of passionate curiosity, though the people whispering behind my back never ask what is this Róbert Valzer chap up to, what in God’s name does he think he is doing continually walking everywhere, no, they never get round to asking that question nor ever will, though the whole point is to know why one is walking, the answer to which, if I may repeat myself, is that it is a matter of curiosity walking as I do, for example right now on the Day of the Dead, because the Day of the Dead is something that greatly interests me. Every Day of the Dead is different from the one before and I wouldn’t miss any Day of the Dead – why would I miss it, given I was interested in it?

Hungary, 2013.

Light clothes for the season, and a light little hat: marvellous weather. Great crowds on the street, plenty of florists’ stalls, streets swimming in Michaelmas daisies overflowing from florists’ tables, a great tide of Michaelmas daisies, white, pink and yellow, and a great tide of people heading to cemeteries of which we have every kind, Catholic in the first instance but also Protestant, evangelical, even Orthodox, and naturally there are Jewish cemeteries too though it’s a long time since anyone was buried in one of those because they’re full and have been closed so that the neo-Nazis can’t easily get at them. There were altogether 505 Jewish people in this town and all 505 were kicked out. None of them ever returned.

I hate Michaelmas daisies and, I must confess, I am not too keen on people either, in fact you might say I hate people too, or, better still, that I hate people as much as I hate Michaelmas daisies and that is simply because every time I see Michaelmas daisies they remind me of people rather than of Michaelmas daisies, and every time I see people I always think of Michaelmas daisies not of people.

There is so much life in cemeteries.

My walk first takes me through the Catholic cemetery, then through the Protestant, the evangelical, and finally through the Orthodox, and I see great crowds of people, which is very strange, and I ask myself when all this visiting of cemeteries became so popular? It certainly wasn’t the case under Kádár: cemeteries were nowhere near so crowded then. Now there are garlands of Michaelmas daisies hanging above family graves because you can’t help noticing whole families coming to festoon the graves in Michaelmas daisies, little children, bigger children, even bigger children, mum, dad, widows and widowers, grandchildren, aunts, uncles, anyone capable of being included in this demonstration of just how much people take the fate of these graves to heart. I gaze at the brand new gravestones, made of the finest, most expensive stone, and wonder what will happen on the day of resurrection? There are so many saints here that not one stone will be left standing.

I should add that I never hurry and I never dawdle. That’s not walking. I walk with hands linked behind my back. And I take note of what I see.

The most popular vehicles are those enormous black jeeps that I can see in the distance as I walk through the Catholic cemetery, the Protestant cemetery, the evangelical cemetery and the Orthodox cemetery, on my way to the vast expensive parking lot at the back. Right after these come the BMWs, the Audis, the Lexuses and Chevrolets, but I notice there are fewer Mercedes this year than last and wonder why Mercedes has fallen out of favour with Hungarians? I can’t think why so I walk on. Then come the Volkswagens, the Skodas, the Opels and the Suzukis, and pretty quickly I find myself in the mean streets of the poor because what follows is the truly sad spectacle of cars parked in two long, apparently infinite rows on both sides of the street beyond the vast expensive parking lot, partly because they have been squeezed out, and, let’s be honest, lawfully squeezed out, of the vast expensive parking lot so as not to ruin the view, and partly because they themselves, this rank of pathetic, half-rusted, damaged Peugeots, Renaults, Fords, Toyotas, Dacias and Kias, and look, there are Mercedes too, more than twenty years old of course, all these would like to have a proper paid-for place in the enormous parking lot, that is to say they would love to be new gleaming Peugeots, Renaults and Toyotas, and definitely not more-than-twenty-year-old Mercedes, but can’t be because they are scrap iron, the kind of scrap iron relegated to the dreaming poor, the saddest thing about the dreaming poor being that their desires are exactly the same as the dreams of those in the BMWs, Audis and Lexuses, that they are made of exactly the same stuff as the dreams of these other people and it is just that they have been condemned never to get into any major parking lot for which you have to pay so their vehicles are doomed to remain outside for ever, there on either side of the street, in the dust, with one wheel on the pavement, leaning to one side, like the whole country whose collapse I, Róbert Valzer, hereby predict.

My feet are fit for walking because I have long used La Sportiva boots instead of shoes, Delladio’s La Sportiva being by far the best boots anyone has ever designed, tough enough for me to be perpetually walking, because my footwear needs to be tough enough to last, and now, having passed through the Catholic, the Protestant, the evangelical and Orthodox cemeteries, I am walking through the long disused Jewish cemetery because, for some unknown reason, this is the one day in the year they unlock it, and I take pleasure walking through it because I like walking on these inimitable La Sportivas, so buoyant and light under my feet, and because there are neither Michaelmas daisies nor people here, there’s nothing to hate, and it’s quiet because no one under these stones is ever going to move again and there clearly won’t be any resurrection because the graves are overrun by weeds with only one or two stones here and there daubed with swastikas sprayed on at weekends by the growing tribe of neo-Nazis, who are only doing it as a form of amusement when they can’t kick – they use Doc Martens – the stones over, and I stride on in my spring-soled La Sportiva boots, past the gravestones and think of the dead that lie here, visited by no one, since there isn’t anyone who could visit them, though it’s the end of the Day of the Dead and soon it will be the day allotted to Yahrzeit, so you can sense it’s getting towards winter and I walk on while slowly it begins to snow, great flakes of it, and I am just getting the feel of those La Sportiva boots treading over snow when – though God knows I have nothing to do with the world-famous Robert Walser – my heart starts to ache, in fact my whole chest aches, and my steps do not slow, but speed up on account of my sudden pain, the steps ever shorter as I hurry on, but it’s all in vain, I start waving my arms and swaying then fall flat on my face and lie out at full length – my body immobile, my hat rolling away and it is only this body and the hat that remain on the snow for a while, along, of course, with my footprints, until they find me and take me away somewhere, and soon even the memorable footprints of those excellent La Sportiva boots begin to melt, because it’s spring and no one will do my walking for me.