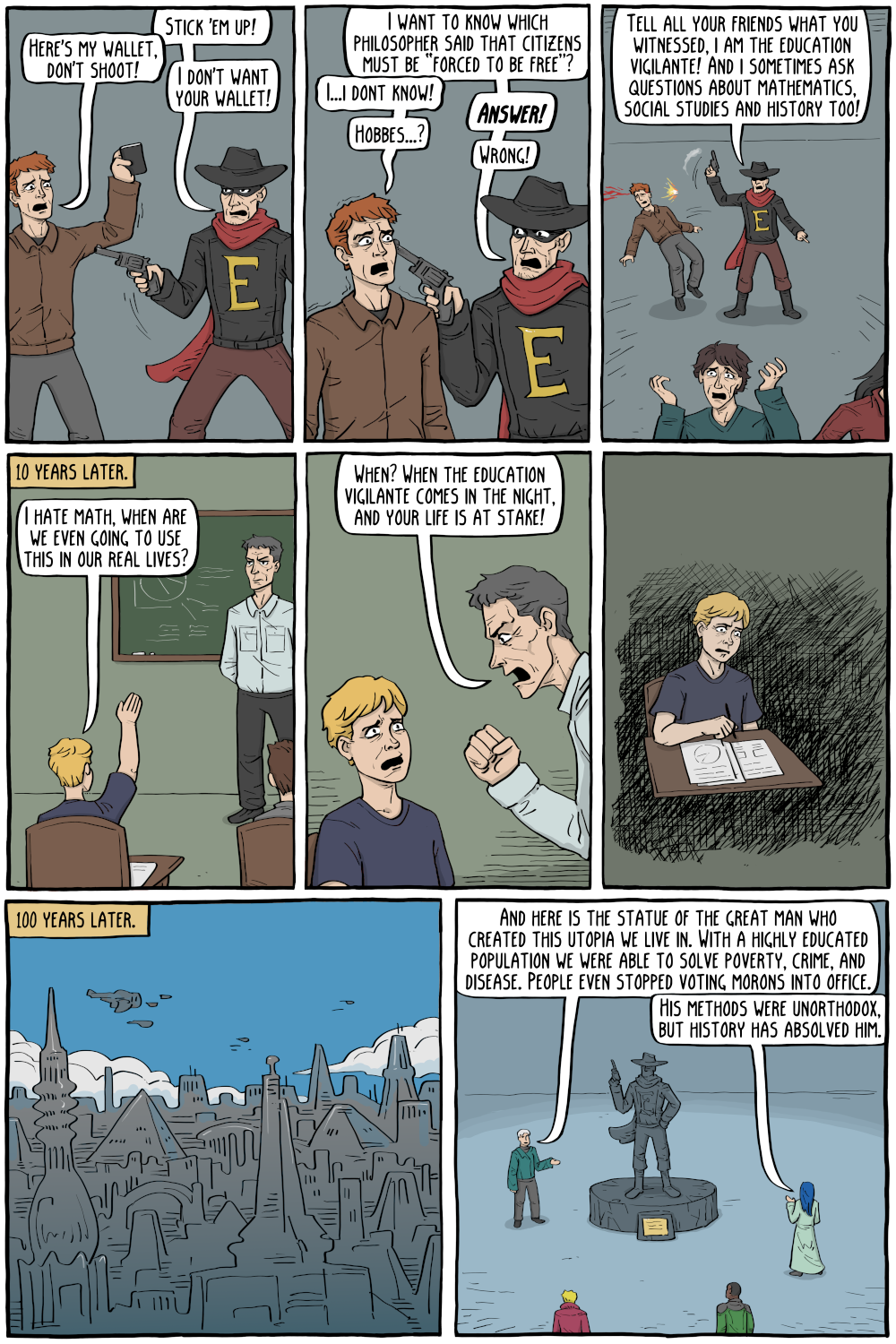

In the essay below from 1988, the iconic American writer, philosopher, and scientist Isaac Asimov addresses the comforting myth that being ‘wrong’ always means starting from zero, arguing instead that knowledge evolves in degrees rather than absolutes. A wonderful piece that will make you feel less certain about binary right/wrong thinking. “How much is 2 + 2? Suppose Joseph says: 2 + 2 = purple, while Maxwell says: 2 + 2 = 17. Both are wrong but isn’t it fair to say that Joseph is wronger than Maxwell? Suppose you said: 2 + 2 = an integer. You’d be right, wouldn’t you? Or suppose you said: 2 + 2 = an even integer. You’d be righter. Or suppose you said: 2 + 2 = 3.999. Wouldn’t you be nearly right?”

The Relativity of Wrong

I received a letter from a reader the other day. It was handwritten in crabbed penmanship so that it was very difficult to read. Nevertheless, I tried to make it out just in case it might prove to be important.

In the first sentence, he told me he was majoring in English Literature, but felt he needed to teach me science. (I sighed a bit, for I knew very few English Lit majors who are equipped to teach me science, but I am very aware of the vast state of my ignorance and I am prepared to learn as much as I can from anyone, however low on the social scale, so I read on.)

It seemed that in one of my innumerable essays, here and elsewhere, I had expressed a certain gladness at living in a century in which we finally got the basis of the Universe straight.

I didn’t go into detail in the matter, but what I meant was that we now know the basic rules governing the Universe, together with the gravitational interrelationships of its gross components, as shown in the theory of relativity worked out between 1905 and 1916. We also know the basic rules governing the subatomic particles and their interrelationships, since these are very neatly described by the quantum theory worked out between 1900 and 1930. What’s more, we have found that the galaxies and clusters of galaxies are the basic units of the physical Universe, as discovered between 1920 and 1930.

These are all twentieth-century discoveries, you see.

The young specialist in English Lit, having quoted me, went on to lecture me severely on the fact that in every century people have thought they understood the Universe at last, and in every century they were proven to be wrong. It follows that the one thing we can say about out modern “knowledge” is that it is wrong.

The young man then quoted with approval what Socrates had said on learning that the Delphic oracle had proclaimed him the wisest man in Greece. “If I am the wisest man,” said Socrates, “it is because I alone know that I know nothing.” The implication was that I was very foolish because I knew a great deal.

Alas, none of this was new to me. (There is very little that is new to me; I wish my corresponders would realize this.) This particular thesis was addressed to me a quarter of a century ago by John Campbell, who specialized in irritating me. He also told me that all theories are proven wrong in time.

My answer to him was, “John, when people thought the Earth was flat, they were wrong. When people thought the Earth was spherical, they were wrong. But if you think that thinking the Earth is spherical is just as wrong as thinking the Earth is flat, then your view is wronger than both of them put together.”

The basic trouble, you see, is that people think that “right” and “wrong” are absolute; that everything that isn’t perfectly and completely right is totally and equally wrong.

However, I don’t think that’s so. It seems to me that right and wrong are fuzzy concepts, and I will devote this essay to an explanation of why I think so.

First, let me dispose of Socrates because I am sick and tired of this pretense that knowing you know nothing is a mark of wisdom.

No one knows nothing. In a matter of days, babies learn to recognize their mothers.

Socrates would agree, of course, and explain that knowledge of trivia is not what he means. He means that in the great abstractions over which human beings debate, one should start without preconceived, unexamined notions, and that he alone knew this. (What an enormously arrogant claim!)

In his discussions of such matters as “What is justice?” or “What is virtue?” he took the attitude that he knew nothing and had to be instructed by others. (This is called “Socratic irony,” for Socrates knew very well that he knew a great deal more than the poor souls he was picking on.) By pretending ignorance, Socrates lured others into propounding their views on such abstractions. Socrates then, by a series of ignorant-sounding questions, forced the others into such a mélange of self-contradictions that they would finally break down and admit they didn’t know what they were talking about.

It is the mark of the marvelous toleration of the Athenians that they let this continue for decades and that it wasn’t till Socrates turned seventy that they broke down and forced him to drink poison.

Now where do we get the notion that “right” and “wrong” are absolutes? It seems to me that this arises in the early grades, when children who know very little are taught by teachers who know very little more.

Young children learn spelling and arithmetic, for instance, and here we tumble into apparent absolutes.

How do you spell “sugar?” Answer: s-u-g-a-r. That is right. Anything else is wrong.

How much is 2 + 2? The answer is 4. That is right. Anything else is wrong.

Having exact answers, and having absolute rights and wrongs, minimizes the necessity of thinking, and that pleases both students and teachers. For that reason, students and teachers alike prefer short-answer tests to essay tests; multiple-choice over blank short-answer tests; and true-false tests over multiple-choice.

But short-answer tests are, to my way of thinking, useless as a measure of the student’s understanding of a subject. They are merely a test of the efficiency of his ability to memorize.

You can see what I mean as soon as you admit that right and wrong are relative.

How do you spell “sugar?” Suppose Alice spells it p-q-z-z-f and Genevieve spells it s-h-u-g-e-r. Both are wrong, but is there any doubt that Alice is wronger than Genevieve? For that matter, I think it is possible to argue that Genevieve’s spelling is superior to the “right” one.

Or suppose you spell “sugar”: s-u-c-r-o-s-e, or C12H22O11. Strictly speaking, you are wrong each time, but you’re displaying a certain knowledge of the subject beyond conventional spelling.

Suppose then the test question was: how many different ways can you spell “sugar?” Justify each.

Naturally, the student would have to do a lot of thinking and, in the end, exhibit how much or how little he knows. The teacher would also have to do a lot of thinking in the attempt to evaluate how much or how little the student knows. Both, I imagine, would be outraged.

Again, how much is 2 + 2? Suppose Joseph says: 2 + 2 = purple, while Maxwell says: 2 + 2 = 17. Both are wrong but isn’t it fair to say that Joseph is wronger than Maxwell?

Suppose you said: 2 + 2 = an integer. You’d be right, wouldn’t you? Or suppose you said: 2 + 2 = an even integer. You’d be righter. Or suppose you said: 2 + 2 = 3.999. Wouldn’t you be nearly right?

If the teacher wants 4 for an answer and won’t distinguish between the various wrongs, doesn’t that set an unnecessary limit to understanding?

Suppose the question is, how much is 9 + 5?, and you answer 2. Will you not be excoriated and held up to ridicule, and will you not be told that 9 + 5 = 14?

If you were then told that 9 hours had pass since midnight and it was therefore 9 o’clock, and were asked what time it would be in 5 more hours, and you answered 14 o’clock on the grounds that 9 + 5 = 14, would you not be excoriated again, and told that it would be 2 o’clock? Apparently, in that case, 9 + 5 = 2 after all.

Or again suppose, Richard says: 2 + 2 = 11, and before the teacher can send him home with a note to his mother, he adds, “To the base 3, of course.” He’d be right.

Here’s another example. The teacher asks: “Who is the fortieth President of the United States?” and Barbara says, “There isn’t any, teacher.”

“Wrong!” says the teacher, “Ronald Reagan is the fortieth President of the United States.”

“Not at all,” says Barbara, “I have here a list of all the men who have served as President of the United States under the Constitution, from George Washington to Ronald Reagan, and there are only thirty-nine of them, so there is no fortieth President.”

“Ah,” says the teacher, “but Grover Cleveland served two nonconsecutive terms, one from 1885 to 1889, and the second from 1893 to 1897. He counts as both the twenty-second and twenty-fourth President. That is why Ronald Reagan is the thirty-ninth person to serve as President of the United States, and is, at the same time, the fortieth President of the United States.”

Isn’t that ridiculous? Why should a person be counted twice if his terms are nonconsecutive, and only once if he served two consecutive terms? Pure convention! Yet Barbara is marked wrong—just as wrong as if she had said that the fortieth President of the United States is Fidel Castro.

Therefore, when my friend the English Literature expert tells me that in every century scientists think they have worked out the Universe and are always wrong, what I want to know is how wrong are they? Are they always wrong to the same degree? Let’s take an example.

In the early days of civilization, the general feeling was that the Earth was flat.

This was not because people were stupid, or because they were intent on believing silly things. They felt it was flat on the basis of sound evidence. It was not just a matter of “That’s how it looks,” because the Earth does not look flat. It looks chaotically bumpy, with hills, valleys, ravines, cliffs, and so on.

Of course, there are plains where, over limited areas, the Earth’s surface does look fairly flat. One of those plains is in the Tigris-Euphrates area where the first historical civilization (one with writing) developed, that of the Sumerians.

Perhaps it was the appearance of the plain that may have persuaded the clever Sumerians to accept the generalization that the Earth was flat; that if you somehow evened out all the elevations and depressions, you would be left with flatness. Contributing to the notion may have been the fact that stretches of water (ponds and lakes) looked pretty flat on quiet days.

Another way of looking at it is to ask what is the “curvature” of Earth’s surface. Over a considerable length, how much does the surface deviate (on the average) from perfect flatness. The flat-Earth theory would make it seem that the surface doesn’t deviate from flatness at all, that its curvature is 0 to the mile.

Nowadays, of course, we are taught that the flat-Earth theory is wrong; that it is all wrong, terribly wrong, absolutely. But it isn’t. The curvature of the Earth is nearly 0 per mile, so that although the flat-Earth theory is wrong, it happens to be nearly right. That’s why the theory lasted so long.

There were reasons, to be sure, to find the flat-Earth theory unsatisfactory and, about 350 B.C., the Greek philosopher Aristotle summarized them. First, certain stars disappeared beyond the Southern Hemisphere as one traveled north, and beyond the Northern Hemisphere as one traveled south. Second, the Earth’s shadow on the Moon during a lunar eclipse was always the arc of a circle. Third, here on Earth itself, ships disappeared beyond the horizon hull-first in whatever direction they were traveling.

All three observations could not be reasonably explained if the Earth’s surface were flat, but could be explained by assuming the Earth to be a sphere.

What’s more, Aristotle believed that all solid matter tended to move toward a common center, and if solid matter did this, it would end up as a sphere. A given volume of matter is, on the average, closer to a common center if it is a sphere than if it is any other shape whatever.

About a century after Aristotle, the Greek philosopher Eratosthenes noted that the Sun cast a shadow of different lengths at different latitudes (all the shadows would be the same length if the Earth’s surface were flat). From the difference in shadow length, he calculated the size of the earthly sphere and it turned out to be 25,000 miles in circumference.

The curvature of such a sphere is about 0.000126 per mile, a quantity very close to 0 per mile as you can see, and one not easily measured by the techniques at the disposal of the ancients. The tiny difference between 0 and 0.000126 accounts for the fact that it took so long to pass from the flat Earth to the spherical Earth.

Mind you, even a tiny difference, such at that between 0 and 0.000126, can be extremely important. That difference mounts up. The Earth cannot be mapped over large areas with any accuracy at all if the difference isn’t taken into account and if the Earth isn’t considered a sphere rather than a flat surface. Long ocean voyages can’t be undertaken with any reasonable way of locating one’s own position in the ocean unless the Earth is considered spherical rather than flat.

Furthermore, the flat Earth presupposes the possibility of an infinite Earth, or of the existence of an “end” to the surface. The spherical Earth, however, postulates an Earth that is both endless and yet finite, and it is the latter postulate that is consistent with all later findings.

So although the flat-Earth theory is only slightly wrong and is a credit to its inventors, all things considered, it is wrong enough to be discarded in favor of the spherical-Earth theory.

And yet is the Earth a sphere?

No, it is not a sphere; not in the strict mathematical sense. A sphere has certain mathematical properties—for instance, all diameters (that is, all straight lines that pass from one point on its surface, through the center, to another point on its surface) have the same length.

That, however, is not true of the Earth. Various diameters of the Earth differ in length.

What gave people the notion the Earth wasn’t a true sphere? To begin with, the Sun and the Moon have outlines that are perfect circles within the limits of measurement in the early days of the telescope. This is consistent with the supposition that the Sun and Moon are perfectly spherical in shape.

However, when Jupiter and Saturn were observed by the first telescopic observers, it became quickly apparent that the outlines of those planets were not circles, but distinct ellipses. That meant that Jupiter and Saturn were not true spheres.

Isaac Newton, toward the end of the seventeenth century, showed that a massive body would form a sphere under the pull of gravitational forces (exactly as Aristotle had argued), but only if it were not rotating. If it were rotating, a centrifugal effect would be set up which would lift the body’s substance against gravity, and the effect would be greater the closer to the equator you progressed. The effect would also be greater the more rapidly a spherical object rotated and Jupiter and Saturn rotated very rapidly indeed.

The Earth rotated much more slowly than Jupiter or Saturn so the effect should be smaller, but it should still be there. Actual measurements of the curvature of the Earth were carried out in the eighteenth century and Newton was proved correct.

The Earth has an equatorial bulge, in other words. It is flattened at the poles. It is an “oblate spheroid” rather than a sphere. This means that the various diameters of the earth differ in length. The longest diameters are any of those that stretch from one point on the equator to an opposite point on the equator. The “equatorial diameter” is 12,755 kilometers (7,927 miles). The shortest diameter is from the North Pole to the South Pole and this “polar diameter” is 12,711 kilometers (7,900 miles).

The difference between the longest and shortest diameters is 44 kilometers (27 miles), and that means that the “oblateness” of the Earth (its departure from true sphericity) is 44/12,755, or 0.0034. This amounts to 1/3 of 1 percent.

To put it another way, on a flat surface, curvature is 0 per mile everywhere. On Earth’s spherical surface, curvature is 0.000126 per mile everywhere (or 8 inches per mile). On Earth’s oblate spheroidical surface, the curvature varies from 7.973 inches to the mile to 8.027 inches to the mile.

The correction in going from spherical to oblate spheroidal is much smaller than going from flat to spherical. Therefore, although the notion of the Earth as sphere is wrong, strictly speaking, it is not as wrong as the notion of the Earth as flat.

Even the oblate-spheroidal notion of the Earth is wrong, strictly speaking. In 1958, when the satellite Vanguard 1 was put into orbit about the Earth, it was able to measure the local gravitational pull of the Earth—and therefore its shape—with unprecedented precision. It turned out that the equatorial bulge south of the equator was slightly bulgier than the bulge north of the equator, and that the South Pole sea level was slightly nearer the center of the Earth than the North Pole sea level was.

There seemed no other way of describing this than by saying the Earth was pearshaped and at once many people decided that the Earth was nothing like a sphere but was shaped like a Bartlett pear dangling in space. Actually, the pearlike deviation from oblate-spheroid perfect was a matter of yards rather than miles and the adjustment of curvature was in the millionths of an inch per mile.

In short, my English Lit friend, living in a mental world of absolute rights and wrongs, may be imagining that because all theories are wrong, the Earth may be thought spherical now, but cubical next century, and a hollow icosahedron the next, and a doughnut shape the one after.

What actually happens is that once scientists get hold of a good concept they gradually refine and extend if with a greater and greater subtlety as their instruments of measurement improve. Theories are not so much wrong as incomplete.

This can be pointed out in many other cases than just the shape of the Earth. Even when a new theory seems to represent a revolution, it usually arises out of small refinements. If something more than a small refinement were needed, then the old theory would never have endured.

Copernicus switched from an Earth-centered planetary system to a Sun-centered one. In doing so, he switched from something that was obvious to something that was apparently ridiculous. However, it was a matter of finding better ways of calculating the motion of the planets in the sky and, eventually, the geocentric theory was just left behind. It was precisely because the old theory gave results that were fairly good by the measurement standards of the time that kept it in being so long.

Again, it is because the geological formations of the Earth change so slowly and the living things upon it evolve so slowly that it seemed reasonable at first to suppose that there was no change and that Earth and life always existed as they do today. If that were so, it would make no difference whether Earth and life were billions of years old or thousands. Thousands were easier to grasp.

But when careful observation showed that Earth and life were changing at a rate that was very tiny but not zero, then it became clear that Earth and life had to be very old. Modern geology came into being, and so did the notion of biological evolution.

If the rate of change were more rapid, geology and evolution would have reached their modern state in ancient times. It is only because the difference between the rate of change in a static Universe and the rate of change in an evolutionary one is that between zero and very nearly zero that the creationists can continue propagating their folly.

Again, how about the two great theories of the twentieth century; relativity and quantum mechanics?

Newton’s theories of motion and gravitation were very close to right, and they would have been absolutely right if only the speed of light were infinite. However, the speed of light is finite, and that had to be taken into account in Einstein’s relativistic equations, which were an extension and refinement of Newton’s equations.

You might say that the difference between infinite and finite is itself infinite, so why didn’t Newton’s equations fall to the ground at once? Let’s put it another way, and ask how long it takes light to travel over a distance of a meter.

If light traveled at infinite speed, it would take light 0 seconds to travel a meter. At the speed at which light actually travels, however, it takes it 0.0000000033 seconds. It is that difference between 0 and 0.0000000033 that Einstein corrected for.

Conceptually, the correction was as important as the correction of Earth’s curvature from 0 to 8 inches per mile was. Speeding subatomic particles wouldn’t behave the way they do without the correction, nor would particle accelerators work the way they do, nor nuclear bombs explode, nor the stars shine. Nevertheless, it was a tiny correction and it is no wonder that Newton, in his time, could not allow for it, since he was limited in his observations to speeds and distances over which the correction was insignificant.

Again, where the prequantum view of physics fell short was that it didn’t allow for the “graininess” of the Universe. All forms of energy had been thought to be continuous and to be capable of division into indefinitely smaller and smaller quantities.

This turned out to be not so. Energy comes in quanta, the size of which is dependent upon something called Planck’s constant. If Planck’s constant were equal to 0 erg-seconds, then energy would be continuous, and there would be no grain to the Universe. Planck’s constant, however, is equal to 0.000000000000000000000000066 erg-seconds. That is indeed a tiny deviation from zero, so tiny that ordinary questions of energy in everyday life need not concern themselves with it. When, however, you deal with subatomic particles, the graininess is sufficiently large, in comparison, to make it impossible to deal with them without taking quantum considerations into account.

Since the refinements in theory grow smaller and smaller, even quite ancient theories must have been sufficiently right to allow advances to be made; advances that were not wiped out by subsequent refinements.

The Greeks introduced the notion of latitude and longitude, for instance, and made reasonable maps of the Mediterranean basin even without taking sphericity into account, and we still use latitude and longitude today.

The Sumerians were probably the first to establish the principle that planetary movements in the sky exhibit regularity and can be predicted, and they proceeded to work out ways of doing so even though they assumed the Earth to be the center of the Universe. Their measurements have been enormously refined but the principle remains.

Newton’s theory of gravitation, while incomplete over vast distances and enormous speeds, is perfectly suitable for the Solar System. Halley’s Comet appears punctually as Newton’s theory of gravitation and laws of motion predict. All of rocketry is based on Newton, and Voyager II reached Uranus within a second of the predicted time. None of these things were outlawed by relativity.

In the nineteenth century, before quantum theory was dreamed of, the laws of thermodynamics were established, including the conservation of energy as first law, and the inevitable increase of entropy as the second law. Certain other conservation laws such as those of momentum, angular momentum, and electric charge were also established. So were Maxwell’s laws of electromagnetism. All remained firmly entrenched even after quantum theory came in.

Naturally, the theories we now have might be considered wrong in the simplistic sense of my English Lit correspondent, but in a much truer and subtler sense, they need only be considered incomplete.

For instance, quantum theory has produced something called “quantum weirdness” which brings into serious question the very nature of reality and which produces philosophical conundrums that physicists simply can’t seem to agree upon. It may be that we have reached a point where the human brain can no longer grasp matters, or it may be that quantum theory is incomplete and that once it is properly extended, all the “weirdness” will disappear.

Again, quantum theory and relativity seem to be independent of each other, so that while quantum theory makes it seem possible that three of the four known interactions can be combined into one mathematical system, gravitation—the realm of relativity—as yet seems intransigent.

If quantum theory and relativity can be combined, a true “unified field theory” may become possible.

If all this is done, however, it would be a still finer refinement that would affect the edges of the known—the nature of the big bang and the creation of the Universe, the properties at the center of black holes, some subtle points about the evolution of galaxies and supernovas, and so on.

Virtually all that we know today, however, would remain untouched and when I say I am glad that I live in a century when the Universe is essentially understood, I think I am justified.